I wrote this essay in April of 2023 as a part of my final portfolio for the graduate-level course ILS Z604 Folklore Archives at Indiana University. The aim was to give an overview of how the IU Folklore Archives, a significant repository of midwestern folk culture, currently exists through various Indiana University archives. Although this presents challenges to conducting research, the online finding aids have the potential to stitch the separate collections back into a cohesive whole.

Introduction

The Indiana University Folklore Archives represents one of the most valuable, and yet underutilized collections held at the Indiana University Bloomington campus. For over six decades, the IU Folklore Archives has served the Indiana University research community through their extensive collections on midwestern folklore and the important folklorists who wrote and collected the materials. The personal manuscripts from folklorists such as Richard Dorson, Henry Glassie, and Warren E. Roberts make up a portion of the archive, while the bulk of the materials were created by university students enrolled in folklore courses. The materials offer expansive insight into traditions, beliefs, and customs that are either extinct or neglected by scholarly communities today.

Since its unofficial founding in 1957, the Archive has continually been relocated and modified to fit changing funds and attitudes in relation to folkloristics. The IU Folklore Archives currently exists in several places scattered around the IU Bloomington campus and this has significantly impacted how students and faculty interact with the materials today. It is greatly important to understand how the Archives exists today because it will determine how users interact with them in the future. The archived materials have tremendous potential to enhance how Bloomington curators, librarians, teachers, and community members choose to engage with their traditional past.

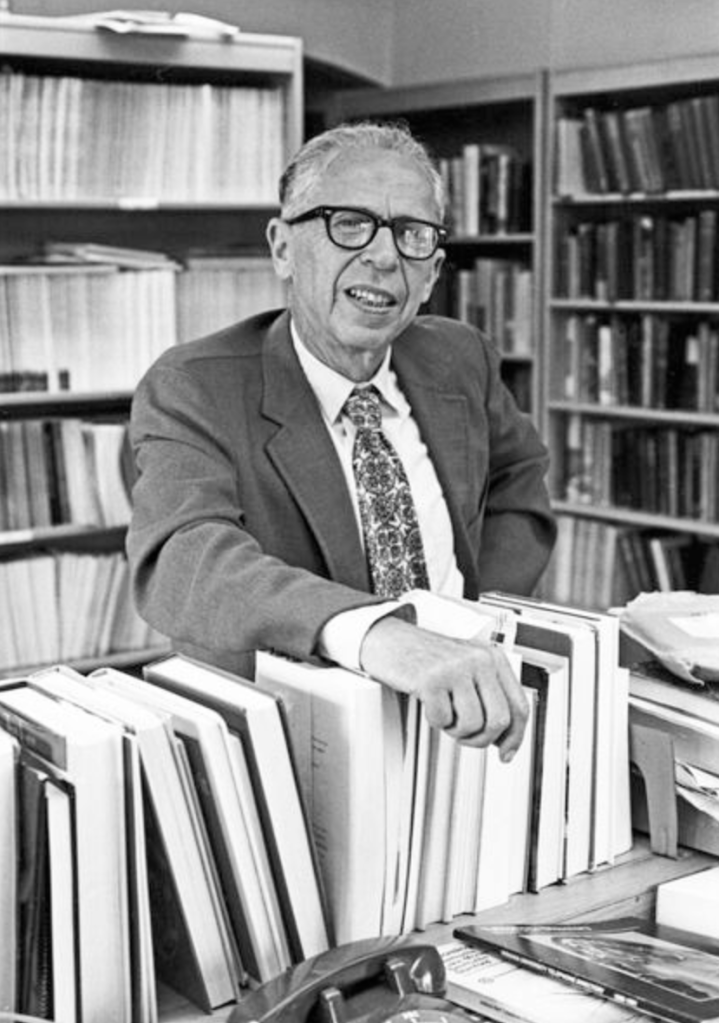

Richard Dorson

The beginnings of the IU Folklore Archives can be traced back to the 1940s when the American folklorist Richard Dorson was instructing at Michigan State University. From 1947 to 1956, Dorson conducted folklore courses where the students were instructed to collect their own folklore materials. [1] This was the genesis of the collection. Materials were collected from all over the midwest and occasionally students participated in trips abroad to collect folklore. In 1957, Dorson accepted a position at Indiana University and he brought with him his student manuscripts, as well as his system for collecting folklore.

Richard Dorson was an incredibly significant figure because his method for collecting materials produced the extensive collections not seen before at Indiana University. By arriving in Bloomington, Dorson also became the chairman of the Folklore Committee at Indiana University, forever shaping the future of folkloristics at Indiana University. (76) [2] Before Dorson, W. Edson Richmond, and Warren Roberts began instructing their students to collect folklore materials, remnants of Hoosier folk culture were not being systematically collected at an academic level. The hundreds of students enrolled in these courses changed the narrative that the stories and traditions of Indiana were worth preserving for academic study. Writing in 1961, Joseph Hickerson, author of “Hoosier Materials in the Indiana University Folklore Archive”, argued “the Indiana University Folklore Archive offers ample proof that Indiana abounds with folklore in many forms” (82) and that there are still many unexplored fields of study.

Current State of Archives

The IU Folklore Archives had grown to encompass decades worth of field transcriptions, which equated to over 200,000 records. The student manuscript files, which made up the bulk of the collections, were divided into three large collections: the Michigan State University Folklore Collection, Pre 1967 Indiana University Collection, and the Student Manuscripts 1967+, which cover materials IU students collected into the 1990s. [3] Students and faculty used the Archives to consult these student collections, but also to reference folklore journals, newsletters, and multimedia materials. [4] One of the largest obstacles the Archives were facing in this period was that much of the materials were not cataloged and not accessible to users. The student workers made up the majority of the staff and there were few full-time workers to counteract the high turnover rate.

However, beginning in the 1990s, the Archives began to significantly change due to university budget restraints and a continued lack of experienced staff to operate the archive. [5] Ultimately, the Archives closed and the materials at its physical location were shrink wrapped and relocated to off-campus storage. The Indiana University Folklore Department was unable to sustain support and interest that previous generations, which included Richard Dorson, Warren Roberts, Henry Glassie, George List, and W. Edson Richmond, had originally generated. After nearly a decade, successful efforts were made to revive the IU Folklore Archives by the Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology and the School of Library and Information Science. [6]Degree paths were established between the two schools, thus making the Archives’ collections valuable research materials for students and faculty. The University Archives, located in Wells Library, the IU Archives of Traditional Music, located in Morrison Hall, and the Lilly Library received portions of the Archives’ collections.

The capacities in which the IU Folklore Archives materials exist today is unclear. The bulk of the Student Manuscripts collections are held at the University Archives, since their collection policies align with preserving materials related to student life at Indiana University. The Lilly Library preserves the private collections related to IU’s folklore professors, such as Dorson, Roberts, Glassie, and Richmond, while the IU Archives of Traditional Music preserves the recordings and multimedia materials created by the students. After conducting a research project that would connect the materials held at the ATM with the University Archives materials, the reality is significantly more unclear.

The reality is that portions of the Student Manuscripts are divided between the student files at the University Archives and the teacher files at the Lilly Library. This means that the dissertations students completed for their materials, occasionally their transcripts of interviews with informants, and final research papers are cataloged under their respective teacher files, since they were completed for courses. This has made creating finding aids for the student manuscripts extremely complicated. Searching within Archives Online has meant individually checking both libraries for desired materials. While the files held at the University Archives usually include the name of the informants and the student researchers, the Lilly materials often excludes this metadata. The genre of the folklore materials is often obscured as well, since both libraries often do not assign subject headings to the records. Currently, searching by the students’ surname and then first name is the most efficient means of finding materials, but is still not an effective search strategy, since there is very little metadata shared between both libraries. Although users should be able to interact with the materials through an online format, users often still need to schedule in-person visits to verify whether they have the correct materials. While the IU Folklore Archives are no longer shrink wrapped, they are still largely inaccessible by users.

Research Potential

The Student Manuscripts collection is comprised of folklore materials that originate from all over the world, but largely from the American midwest. They cover a broad range of genres and present significant opportunities to improve scholarship specifically focused on Hoosier folk studies.

The Indiana University and Michigan State student body did a tremendous job at capturing traditional folk practices from elderly friends and family. The Recipes, 1964-1966 folder from the University Archives records early versions of persimmon pudding, a traditional recipe unique to southern Indiana, and yet not widely known by Hoosiers today. These records offer valuable insight into how resilient these traditions are and whether they were fading by the mid 20th century or still thriving in sections of the state. These collections also record unique local renditions of popular folk stories, such as the phantom hitchhiker or “Indian” tales. Several Child folk ballads are found in the University Archive’s Folksong Collection, 1863-1967, bulk 1955-1967, thus recording the presence of songs that originated from Ireland and the United Kingdom. Collections such as Places – Indiana Counties, 1950-1967 also offer folktales unique to the state. Some tales offer explanations for how Indiana became the “Hoosier state”, offering valuable insight into how people perceived their identity as Hoosiers.

The transcripts also record the traditions of the students themselves. College songs range from drinking songs to moralistic songs that “offer soul-searching advice to wayward students.” (78) [7] They record how students communicated with each other and they reveal how generations of Indiana University students projected meaning into their surrounding environment, creating traditions that have carried on for generations. The song “Moo Moo Purdue #147, 1957-1966” records early examples of students participating in the Indiana-Purdue rivalry, which students continue to participate in today. The Modern Horror Legends, 1956-1974 describes legends that have been transmitted throughout the Bloomington campus since the early 20th century. For instance, “the owl on top of the book store which will supposedly take wing and fly away under similar circumstances” (78) [8] and the older dormitories are abound with ghost stories.

Once these materials are readily accessible, there are significant opportunities to enhance student learning and development through the engagement of folk materials. The surrounding museums, libraries, and cultural centers could greatly benefit from these collections because they would directly impact the creation of new exhibitions, blog posts, and programs. For instance, the Wylie House Museum could consult the traditional recipes collection and prepare programming related to baking in 20th century Indiana. Video demonstrations could be posted to their website or a live demonstration could be planned to encourage the public to engage with their traditional recipes. Furthermore, using the ballads found in the University Archives as reference, the IU Center for Rural Engagement could organize visits to rural counties to record what Child ballads are still being played today. The Folklore Institute’s annual Ghost Walks actively engages with the legends and superstitions collection to promote the knowledge of Indiana University ghost stories. Imitating this type of engagement will promote an awareness of the unique and lively traditions found on campus. Furthermore, those pursuing dual degrees related to fields of library science, museum studies, folkloristics, or ethnomusicology would then benefit from courses that utilize the above mentioned resources. Field-trips to these sites would inspire capstone projects, senior thesis assignments, and future university program initiatives.

Conclusion

The IU Folklore Archives has been underutilized mainly due to the constant changes surrounding the collections. While digital archives have made it easier to make materials more accessible, there remain challenges to making the materials retrievable through an online format. One method of better utilizing the collections is to create effective finding aids that clearly address where materials are located on campus. This remains the largest barrier to access. Once the collections are unlocked, there are boundless opportunities for how these materials can be used by Indiana University.

Footnotes

[1] Dorson, Richard. “New Holdings at the Indiana University Folklore Archives,” The Folklore & Folk Music Archivist 1, no. 1 (1958).

[2] Hickerson, Joseph. “Hoosier Materials in the Indiana University Folklore Archive,” Midwest Folklore 11, no. 2 (1961): https://www.jstor.org/stable/4317908.

[3] Dart, Mary. “Report on the State of the Folklore Archives,” Unpublished, (1991).

[4] Guide to the Indiana University Folklore Archives. Bloomington, Indiana: The Folklore Archives, 1979.

[5] Smith, Moira. “A Brief History of Folklore Archiving at Indiana University,” Unpublished, (2003).

[6] Smith, Moira. “A Brief History of Folklore Archiving at Indiana University,” Unpublished, (2003).

[7] Hickerson, Joseph. “Hoosier Materials in the Indiana University Folklore Archive,” Midwest Folklore 11, no. 2 (1961): https://www.jstor.org/stable/4317908.

[8] Hickerson, Joseph. “Hoosier Materials in the Indiana University Folklore Archive,” Midwest Folklore 11, no. 2 (1961): https://www.jstor.org/stable/4317908.