I began compiling research for this blogpost just before I accepted a full-time archivist position at Purdue University Archives and Special Collections. Three months later, I am happily settled in a new city, marking the first time I have lived away from my hometown of Bloomington, Indiana. This also marked the first time (in a long time) someone in my family chose to permanently move away from southern Indiana for work – the reality for many first generation college graduates. As you will discover in this blogpost, this is only the latest development in how the economy influences migration patterns.

Introduction

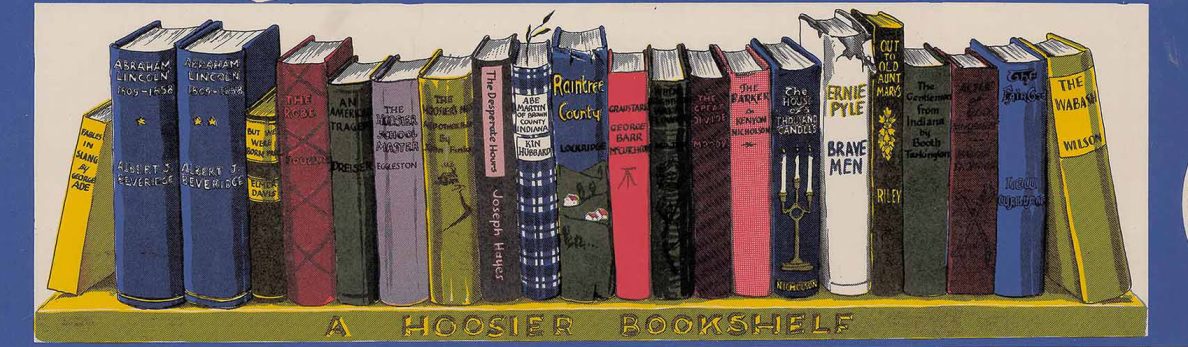

One of my favorite school field trips was visiting the Honey Creek School, a historic one-room schoolhouse that hosts grade school trips in Monroe County. We had the opportunity to spend a day imagining what 19th century and early 20th century life would have been like. It wasn’t until recently that I was struck with how many one-room schools were needed to make school easily accessible to the hundreds of children scattered throughout the county. In fact, there were three one-room schools within walking distance from where I grew up in Van Buren Township. The fact was that the lives of 19th century Hoosiers were largely spent within walking distance of their homes.

Consider this. The series Memories of Hoosier Homemakers edited by Eleanor Arnold gives tremendous insight into how the lives of 19th century and early 20th century Hoosiers were shaped entirely by their small, rural communities. Fourth in the series, Girlhood Days features interviews with women who were born before the 1920s, preserving their memories of a way of life before a majority of Hoosiers migrated to urban centers. One interviewee recalled “watch[ing] the boats on the Ohio River and remember[ing] ‘We thought they came from nowhere and were going into another world’” (5), offering a vivid image of how the physical boundaries of their lives were smaller. The distance you walked to school, the general store, or to town marked the boundary in which you spent most of your life.

Using the Neeld family from my paternal side of the family, I want to explore how the Kirby community of Van Buren Township was actively shaped by Monroe County’s earliest pioneer families. An exercise that is helpful in understanding how my family’s ancestral line was shaped by Indiana’s steadily growing industrial economy.

The Neeld Family

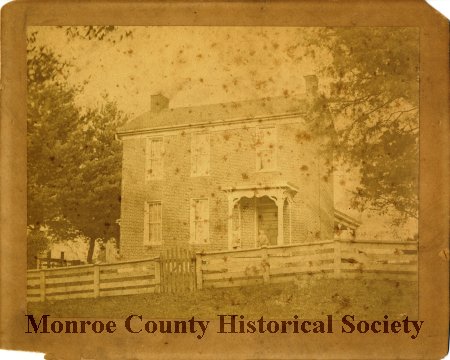

Approximately around 1820, Benjamin Neeld migrated from Harrrodsburg, Kentucky to Monroe County, Indiana with his wife Sarah Hall Denny, making the Neeld family the earliest Monroe County settlers I am related to. The early to mid 1800s marked the period in which thousands of Upland Southerners moved into the Midwest for cheaper land. Neeld was quick to make an impact in his local community of Kirby. His farmstead located off Kirby Road and State Road 48 in Van Buren Township and was one of several prosperous family farms located in Kirby. Neeld was proactive in helping establish the pillars of the community – he kept a blacksmith forge on his property, aided in the construction of the Cross Roads Methodist Church, and donated materials for the rebuilding of the Kirby School. He was also one of the few individuals who also aided in the development of Monroe County by welding the axes that were used to cut the timber for the first courthouse. Benjamin lived the rest of his life on the farmstead until 1868. His life is characteristic of the early pioneer who helped build up his local community.

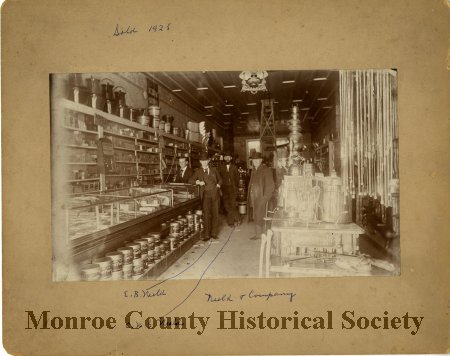

It was the beginning of the 20th century when life in unincorporated communities like Kirby rapidly started to change. In Hoosiers: A New History, James H. Madison provides insight into how a rapidly industrialized economy influenced migration patterns in Indiana. He notes that while the “locally owned small mills and shops and individual craftsmen remained”, such as Benjamin’s blacksmith, “they played a diminished role in the new economy.” (178) Benjamin’s children, namely Cyrus Nutt Simpson Neeld, were eager to expand their business and appeal to larger markets, rather than just to their local community. Born in 1844, Cyrus was raised as a farmer, but after the Civil War he established the Baker Neeld furniture store and then later founded his own hardware store in downtown Bloomington by the 1890s. His permanent move to downtown Bloomington with his wife Sarah Julia Borland in 1900 marked a significant change in how my own family responded to the changing economy of Indiana. For the first time, the farming equipment Cyrus was selling from his hardware store was likely produced by large manufacturing companies, rather than local craftsmen like his father.

Two generations later, the Neelds continued to live in town. Cyrus and Sarah’s great grandchild Julianna Neeld, my great grandmother, was born in 1912 on the east side of downtown Bloomington. Later in life, she recalled taking the Illinois Central Railroad to the Kirby station from Bloomington to visit the family farm, giving her a chance to see the “country”. The Kirby station was three miles west of the Bloomington station and was located where the train tracks intersect with Kirby Road, near the Monroe County Airport. Julianna likely continued to visit the farm until it was sold to the Bunger family – removing any reason for a Neeld to return to the Kirby community. This was far from abnormal. According to…, most Monroe County families were finding steadier work at Indiana University, the limestone mills, and the RCA plant. My grandmother, Shirley Ann Cohee, the great grand-daughter of Benjamin Neeld, worked a long career as a secretary at Indiana University.

Closing Thoughts

A few surprises. I was initially shocked how quickly farming was abandoned by the Neelds. After further consideration, it was natural for the son of a blacksmith to pursue his own farming equipment business. Life in Kirby was exchanged for a more comfortable life in Bloomington – the Neelds followed the cues of an industrial economy, as did many Hoosier families around the turn of the century.

The Kirby community did hang in there for a little bit after the Neelds moved to town. The consolidation of schools in the 1950s made one-room schools obsolete. Grandview Elementary was properly resourced with school supplies and teachers, unlike the old Kirby School. I encourage anyone interested to look into Chapter [blank] in James Madison’s Hoosiers for more information on how the teacher’s union campaigned for standardized learning within the state and altered the quality of education around the turn of the century. This of course erased the community element in Kirby. Tidbits from Echoes from School House explore how baseball games, sledding, and snowball fights were common sights driving down Kirby Road before school consolidation. At the intersection of Kirby and Highway 48, there was also a grocery shop I was unable to find any record of.

It’s fascinating driving through Kirby now. It’s mostly residential homes and is the site of the Monroe County Airport. Although the Neeld house was demolished in 2015, three homes built by the Bungers, a prominent farming family in the area, still stand. I highly encourage taking a moment to drive down Kirby Road and consider how Kirby was the humble starting point for so many families who went on to happy, successful lives elsewhere.

References

Madison, James H. Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014.

Sparks, Lois. Echoes From One-Room Schools: Monroe County, Indiana. Bloomington: AuthorHouse, 2006.

Arnold, Eleanor Arnold. Girlhood Days: Memories of Hoosier Homemakers. Indiana Extension Homemakers association, 1987.

Bowen, B.F.. History of Lawrence and Monroe Counties, Indiana: Their People, Industries, and Institutions, New York: New York Public Library, 1914.

Ehman, Lee, Schlemmer, Elizabeth. “Simpson Neeld Letter: An Echo from the Civil War,” Monroe County Historian, Vol. 2011, No. 6.